The video contained a segment that showed what appeared to be a body falling out of one of the carriages. Later that same day, a bystander used a mobile phone to shoot video footage of derailed train carriages being pulled off the viaduct. But, at 5:00am, a toddler was found alive in one of the carriages. At 4:00am on Sunday morning, the state-owned Xinhua News Agency reported that the accident had resulted in thirty-five fatalities, and that all of the dead had been accounted for. In the early hours of the following morning, the Ministry of Railways in Beijing released a statement blaming the accident on a lightning strike. While most government journalists and information minders enjoyed their Saturday night as usual, news of the crash lit up the microblogosphere. Yangjuan Quanyang’s tweet spread rapidly through the mainland and overseas media it broke the news of the disaster. Help! Train D301 is derailed just near South Wenzhou Station. Everywhere you can hear children crying. The D301 lost four carriages, including two that toppled some forty metres to the ground below from the viaduct on which the crash had occurred. The violent high-speed collision derailed six carriages. As passengers sat waiting for an announcement about the delay, the D3115 was rear-ended by another train – the D301 – which was travelling along the same tracks also en route to Fuzhou, but from the direction of Beijing. Just after 8:00pm, the train stalled near Wenzhou, a city famous for its entrepreneurs and the fabulous wealth they have amassed. On the evening of 23 July, however, she was travelling on one of China’s celebrated new high-speed trains, the D3115, speeding between Hangzhou and Fuzhou on the south-east littoral of the country.

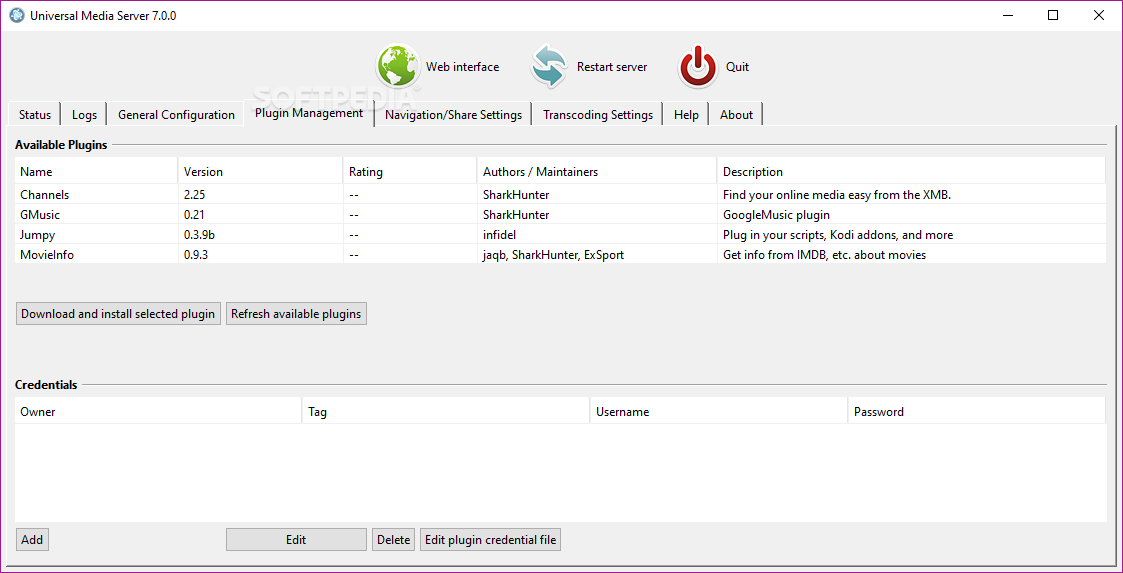

Until late July 2011, most of her tweets were about the mundane details of her daily life. Yangjuan Quanyang’s microblog page is decorated with cute cartoons. As Gloria Davies has noted in Chapter 5, in the People’s Republic of China, Twitter (like Facebook, YouTube, and many other near-universal websites) is inaccessible unless you use a Virtual Private Network (VPN) or other technical tricks to tunnel through the inter-meshed system of Internet roadblocks that is generally referred to as the ‘Great Firewall of China’. She is one of the 250 million people who, in 2011, used Weibo, or microblogs, a Twitter-like service operated by the Internet company Sina. Yangjuan Quanyang is the online moniker of a student at a Beijing university. This was after the authorities had announced a final death toll, and claimed that all bodies had been accounted for. A High-speed Crash Screenshot of a video in which Internet users said they saw a body falling out of a carriage following the Wenzhou train disaster. Proxy servers and a few other technologies can serve the same function.

Because the data is encrypted as it passes through the Great Firewall, it is not identified as objectionable and so the user can access blocked websites. The server connects with the global Internet and then encrypts the traffic again before sending it back to the user’s computer in China. A VPN works by encrypting the Internet traffic from a user’s computer and sending it to a server hosted abroad. Using virtual private networks (VPN), proxy servers or other technical tricks to bypass the Great Firewall so as to gain access to blocked websites is called ‘jumping the Wall’. Jumping the Wall ( fan qiang 翻墙) and Virtual Private Network (VPN) Most Chinese Internet users simply write the English letters GFW when referring to the Great Firewall. Popular global websites restricted by the Great Firewall in 2011 included Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, as well the websites of various dissident groups and activists.

The filtering system that blocks mainland Chinese Internet users from some international websites and web pages.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)